Introduction:

Picture this: It’s the year 2019. Flying cars fill the smog-choked skies of Los Angeles, giant ads bark at you in Japanese, and your biggest concern isn’t rent, it’s whether the person you’re talking to is a soulless robot pretending to be human.

Welcome to Blade Runner, Ridley Scott’s 1982 masterclass in beautifully depressing science fiction. A film so ahead of its time, it managed to out-dystopia most actual dystopias. Also: rain. So much bloody rain.

Let’s take a dive into the cyberpunk misery that changed sci-fi forever and made everyone terrified of AI decades before ChatGPT was a twinkle in the data set.

Table of Contents

The Plot: Philip K. Dick Meets Existential Ennui

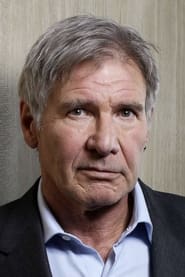

Blade Runner is loosely based on the 1968 novel Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?, which already sounds like something written on a bad acid trip during a blackout. The film follows Rick Deckard (Harrison Ford), a retired “blade runner” forced back into the gig economy to hunt down and “retire” rogue replicants bioengineered humanoids who are stronger, smarter, and possibly more emotionally complex than your ex.

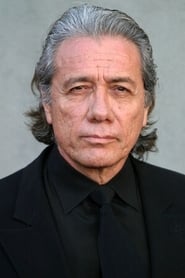

These replicants, led by the bleach-blonde, murder-poetry-quoting Roy Batty (Rutger Hauer), have a four-year lifespan and one hell of an abandonment complex. They return to Earth to confront their creator, because apparently therapy isn’t covered in their synthetic health plan.

Deckard, meanwhile, grumbles his way through morally ambiguous murder with the enthusiasm of a man who just realised he’s out of whisky.

The Aesthetic: Neon Hellscape Chic

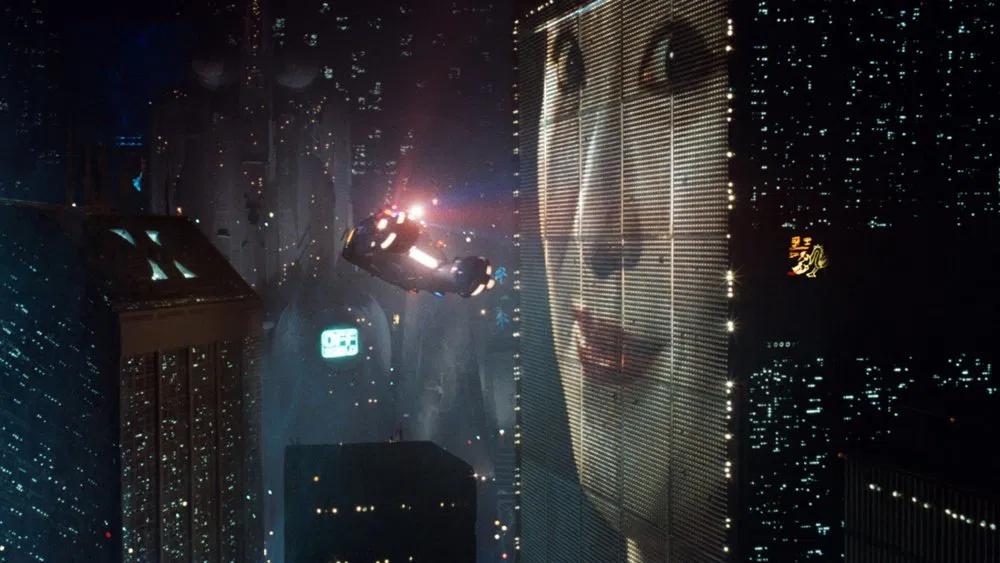

If Blade Runner were a lifestyle brand, it would be “urban decay meets LED showroom.” The film’s vision of Los Angeles in 2019 is all flickering signs, perpetual rain, and a general sense that deodorant was banned by a totalitarian government years ago.

The production design is equal parts breathtaking and filthy, like a perfume ad shot in a sewer. And yet it’s stunning. The visuals are legendary every frame a dark, brooding oil painting smeared with capitalism, pollution, and regret.

This is the future as imagined by people who never thought the 1980s would end. And honestly, it kind of didn’t.

The Characters: Flawed, Frightening and Possibly Robots

Deckard is an antihero in the classic noir mold: tired, disillusioned, and violently competent. He falls for Rachael (Sean Young), a replicant who doesn’t know she’s a replicant, a plot twist that raises philosophical questions about memory, identity, and whether it’s ethically okay to date a toaster if it has nice hair.

But it’s Rutger Hauer’s Roy Batty who steals the show. A violent, poetic machine-man with daddy issues, Batty delivers the most iconic monologue in sci-fi history (“I’ve seen things you people wouldn’t believe…”) before dying in the rain like a soggy Shakespearean antihero.

His death scene is weirdly emotional, which is impressive for a character who snapped a man’s neck five minutes earlier.

Themes: What Does It Mean to Be Human? (And Other Questions That Will Keep You Awake at 3 AM)

Blade Runner isn’t just about hunting robots. It’s about what it means to be human – if having memories, feelings, and a sense of existential dread makes you real, then congratulations: you too might be a replicant.

The movie doesn’t answer its questions it just tosses them at you like philosophical grenades and leaves you in the rubble to ponder your own fragile sense of identity.

And let’s not forget the moral ambiguity. Everyone’s terrible. The cops are terrible. The replicants are terrible. Deckard is basically a noir-themed hitman. No one’s a hero. It’s like Game of Thrones, but with more neon and fewer dragons.

The Versions: How Many Cuts Is Too Many?

There are approximately 7 different versions of Blade Runner, including the Theatrical Cut (with Harrison Ford narrating like he’s being held at gunpoint), the Director’s Cut (which sort of explains less), and the Final Cut (which Ridley Scott insists is definitive, until he inevitably changes his mind).

The biggest debate? Whether Deckard is secretly a replicant himself. If so, he’s the most bored-looking robot ever assembled.

Why It Still Matters: Warning or Blueprint?

In an era where artificial intelligence is writing essays, generating deepfakes, and probably plotting humanity’s downfall, Blade Runner feels eerily relevant. It’s less a sci-fi film and more a prophecy. The line between human and machine is blurring, corporations still run the world, and yes, the climate is still trying to kill us.

So yeah. Welcome to the future. It’s less Jetsons, more Blade Runner with better Wi-Fi.

My Final Thoughts: Rain, Robots and Ruthless Capitalism

Blade Runner is the kind of film that lingers in your brain like a malware pop-up. It’s dark, moody, and emotionally bruising in the best possible way. If you’re looking for a fast-paced shoot-‘em-up, go watch something with more explosions and fewer existential crises.

But if you want a hauntingly beautiful, deeply cynical look at the future we may already be living in Blade Runner is your grim, neon-lit, synthetic soulmate.

Just don’t watch it expecting answers. Or happiness. Or daylight.

If You Like Blade Runner, I Recommend These Movies:

Ghost in the Shell (1995) – Blade Runner with more wires, less rain, and a philosophical migraine.

Brazil (1985) – A dystopia where bureaucracy is the real replicant, and nothing makes sense on purpose.

Children of Men (2006) – The future’s even bleaker, but the existential gloom feels oddly familiar.

Blade Runner

Deckard

Batty

Rachael

Gaff

Bryant

Pris

Sebastian

Leon