Control (2007): A Film So Bleak, Even the Colour Gave Up

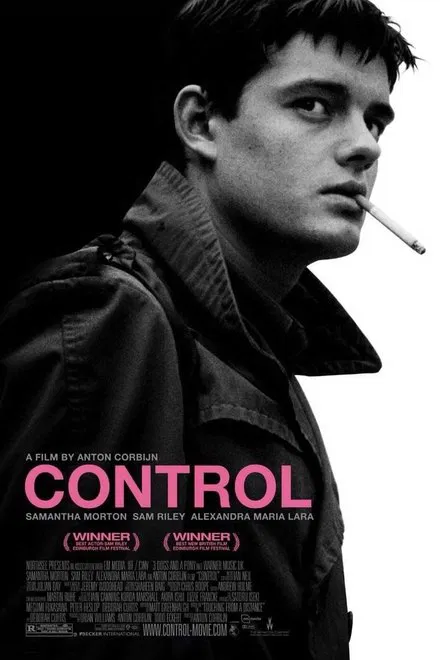

If you ever wanted to know what existential despair would look like with cheekbones, Control is your answer. Directed by Anton Corbijn (famed music photographer and part-time harbinger of stylish sadness), this 2007 biopic of Joy Division frontman Ian Curtis isn’t so much a film as a grayscale gut-punch.

Shot entirely in black and white, because apparently colour was too optimistic, Control charts the brief, brilliant and brutal life of Curtis, played with ghostly intensity by Sam Riley. This isn’t your standard rock ‘n’ roll story full of backstage groupies and guitar-smashing tantrums. No, this is British misery with reverb. It’s a funeral dirge in cinematic form – and it’s utterly mesmerising

Table of Contents

The Plot: Misery Loves Monotone

The film follows Ian Curtis from his teenage years in 1970s Macclesfield (where dreams go to die) through the formation of Joy Division, to his tragic suicide in 1980 at the age of 23. Along the way, there are epileptic fits, doomed romances, suffocating domesticity and the kind of grey skies that make you want to scream into a pillow.

Curtis marries young, has a baby, gets famous and spirals into a cocktail of depression, existential dread and crippling guilt. Not exactly School of Rock, is it? And yet, it’s a spellbinding story – like watching a beautiful car crash in ultra-slow motion.

Sam Riley: Ghost in the Machine

Sam Riley doesn’t so much play Ian Curtis as become him. With a hollow stare and a voice dipped in despair, Riley captures the fragility, the charisma and the all-consuming torment of Curtis without ever slipping into parody. He doesn’t wink at the audience or try to romanticise the pain. He just bleeds it out, one pained twitch at a time.

He even sings live in the film’s performance scenes and somehow manages to make “Transmission” sound like a nervous breakdown with basslines. It’s magnetic and heartbreaking and just a little bit terrifying. Like watching a man drown while everyone claps.

Samantha Morton: Saint in a S**tstorm

As Deborah Curtis, Ian’s long-suffering wife, Samantha Morton is the emotional anchor of the film – or maybe the emotional punching bag. Either way, she’s brilliant. With weary eyes and heartbreaking realism, she portrays a woman desperately trying to understand a man who barely understands himself. Their relationship is less romance, more mutual emotional hostage situation.

Morton plays Deborah not as a passive victim but as someone slowly ground down by love, loyalty and laundry baskets full of unmet needs. You don’t watch this film and think “relationship goals.”

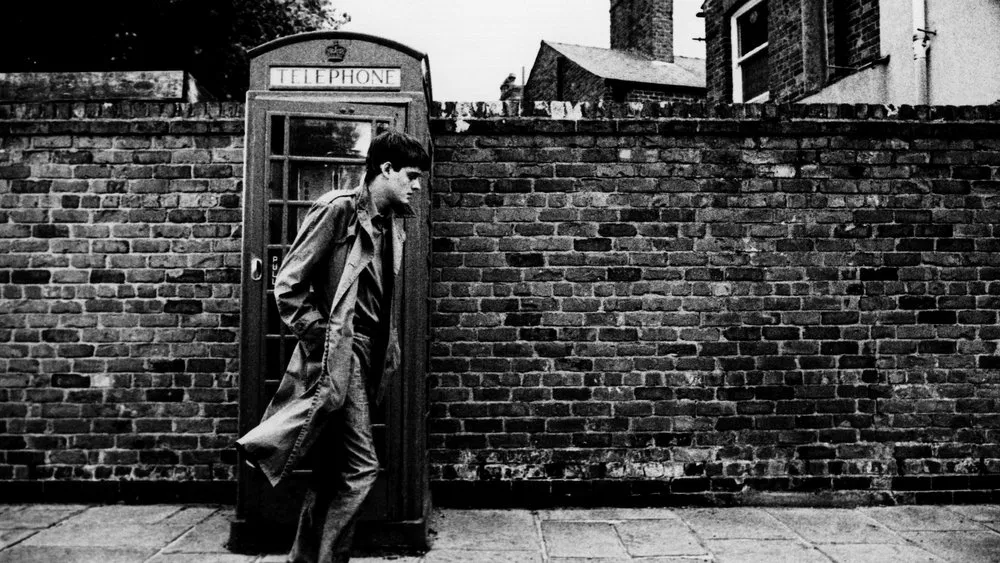

Northern England: Where Hope Goes to Retire

Macclesfield, the film’s setting and Curtis’s real-life stomping ground, isn’t just a backdrop – it’s a co-conspirator. Drab, industrial and permanently overcast, it oozes the kind of energy that makes you want to sigh into your tea and reconsider every decision you’ve ever made.

The film captures the town’s existential inertia so well, you might develop a vitamin D deficiency just watching it. This is kitchen-sink realism with the sink rusting, leaking and giving up entirely.

Anton Corbijn: Bleak is Beautiful

Director Anton Corbijn made his name photographing bands like U2 and Depeche Mode, but with Control, he graduated to making them look cheerful by comparison. His camera lingers like a hangover, capturing moments of silence, shadow and cigarette smoke with haunting elegance.

The black-and-white cinematography isn’t just an aesthetic choice – it’s a character. It wraps the film in a shroud of doom, stripping everything of warmth. Even when the characters laugh (rarely), you feel like the film itself disapproves.

It’s a bold move and one that absolutely pays off. The monochrome palette turns Macclesfield into a post-industrial purgatory and every pub, gig and bedroom feels like it’s been marinated in sorrow.

Style Over Sunshine: Fashion and Fatalism

It’s almost offensive how stylish this misery looks. From Curtis’s iconic trench coat to Annik’s quiet Euro-chic, Control dresses its characters like they’re on the cover of The Sartorial Depressionist. The fashion is stark, timeless and very possibly responsible for a thousand indie bands’ wardrobes.

Corbijn’s eye for composition gives even the bleakest moments a savage beauty. You’ll want to pause scenes just to admire the misery’s symmetry.

Joy Division: Misery with Melody

You don’t need to be a fan of Joy Division to appreciate Control, but it helps if you think dancing should look like a seizure and sound like a panic attack. The band’s rise is shown not as a meteoric explosion but as a grim slog through northern clubland, powered by amphetamine nerves and the kind of lyrics that make Sylvia Plath look chipper.

From “She’s Lost Control” to “Love Will Tear Us Apart,” the songs are like sonic diary entries from a man quietly falling apart. The film doesn’t sanitise or mythologise. It just lets the music breathe – and occasionally scream.

The Sound of Dread: Music as Character

In Control, the soundtrack doesn’t just accompany the story – it practically narrates it. Each song bleeds mood into every scene, from the melancholic hum of David Bowie to the skeletal pulse of Joy Division’s own catalogue. The music isn’t there to lift spirits, it’s there to cradle your emotional collapse in basslines and reverb.

This is a film where the needle drop isn’t cool – it’s devastating. Listening to “Atmosphere” during the final act feels like someone handing you a glass of tears and saying, “Cheers, now drink up.

Mental Illness and Epilepsy: No Metaphors, Just Misery

Control doesn’t use epilepsy as a poetic device. It shows it as what it is: terrifying, isolating and cruelly misunderstood. Curtis’s seizures are depicted with harrowing realism and the toll it takes on his psyche, relationships and stage performances is never underplayed.

Mental illness, likewise, isn’t wrapped in artistic mystique. It’s raw and messy and often silent. There’s no “eureka” moment, no breakthrough – just a slow, tragic unraveling. It’s devastatingly honest.

Romance? More Like Emotional Catastrophe

Enter Annik Honoré (Alexandra Maria Lara), the Belgian journalist who becomes Ian’s lover and moral dilemma. Their affair is tender, doomed and about as cheerful as a Morrissey B-side.

Annik doesn’t play the femme fatale. She’s soft-spoken, empathetic and impossibly European. But instead of offering escape, she becomes another fragment of Curtis’s internal collapse. It’s not a love triangle. It’s a slow-motion heart implosion.

The Suicide Scene: The Ending You Dread and Expect

You know how this ends. From the first frame, there’s a sense of inevitable doom hanging over the film like a damp towel. And yet, when it comes, it still hits hard.

Curtis’s suicide is shown with restraint but no sentimentality. There’s no dramatic score, no last-minute salvation. Just silence, stillness and the crushing weight of despair. It’s a horrible, haunting end to a film that never pretended there was going to be a happy one.

What Control Gets Right: Everything That Hurts

Most music biopics go for triumph over tragedy. Control does the opposite. There’s no redemption arc. No glorious comeback tour. Just a brutally honest portrait of a talented, tormented man crushed by his own mind.

It’s bleak, yes. But it’s also beautiful. There’s a quiet poetry in the pain, an elegance in the suffering. Control is not fun. It’s not uplifting. It’s a film that stares into the abyss, hands you a cigarette and asks if you fancy a cry.

Critics on Control: We’re All Sad Too, Anton

Critics adored Control because it was everything most biopics aren’t: honest, unsentimental and unwilling to spoon-feed you redemption. Empire called it “a masterclass in misery,” while The Guardian described it as “unrelentingly poignant.” Which is critic-speak for: “We cried, it hurt, five stars.”

And yet, Control doesn’t ask for your pity – it just demands your attention. That’s what makes it special. It’s not begging you to feel sorry for Ian Curtis. It’s showing you why he didn’t feel anything at all.

The Legacy: Monochrome Immortality

After Control, Joy Division wasn’t just a cult band. They became mythic. Curtis became the poster boy for tortured artistry. And monochrome became the colour of cool, depressing brilliance.

The film was critically acclaimed, scooping up awards and ruining evenings in equal measure. It launched Sam Riley’s career and cemented Corbijn as a director unafraid to make you feel like your soul’s just been gently stomped on.

Cultural Aftershock: Curtis the Icon, Joy Division the Brand

Since the release of Control, Ian Curtis has been elevated from cult figure to tragic icon and Joy Division have been immortalised on every uni student’s bedroom wall – right between a Bukowski quote and an ashtray full of despair.

The film helped solidify Curtis’s mythology, but also reignited debates about romanticising mental illness and the fetishisation of suffering. Is it art, exploitation, or just British cinema doing what it does best – making you feel profoundly sad and vaguely guilty?

Behind the Scenes Trivia: Bleak But Fascinating

- Shot in Curtis’s actual house: Because why use a set when you can marinate the cast in authentic sorrow?

- Based on Deborah Curtis’s memoir: “Touching from a Distance,” which is every bit as heartbreaking as the film.

- Sam Riley learned to sing like Curtis: Live vocals, no miming, all anguish.

- Anton Corbijn actually knew Joy Division: Which makes the film feel less like a biography and more like a eulogy.

- Won Best Film at Cannes Director’s Fortnight: Proving sadness can be sexy, if you light it properly.

My Final Thoughts: Beauty in the Breakdown

Control is not a film you watch lightly. It’s a cinematic séance. A meditation on the fragility of genius and the quiet violence of depression. It’s harsh, harrowing and hypnotic.

You won’t walk away humming the tunes. You’ll walk away staring at the wall and questioning your life choices. Which, let’s be honest, is exactly what Ian Curtis would have wanted.

So pour yourself something strong, wrap up in a black turtleneck and embrace the cinematic equivalent of a beautiful emotional breakdown.

If You Like Control, I Recommend These Movies:

- Sid & Nancy (1986) – Punk love story meets heroin tragedy. It’s like Romeo and Juliet with more vomit.

- Amy (2015) – The documentary equivalent of crying in the shower.

- Love & Mercy (2014) – Brian Wilson’s breakdown, but with sunshine and Pet Sounds.

- The Devil and Daniel Johnston (2005) – When genius and madness dance awkwardly together.

Control

Ian Curtis

Debbie Curtis

Annik Honoré

Hooky

Rob Greton

Tony Wilson

Bernard Sumner

Steve Morris