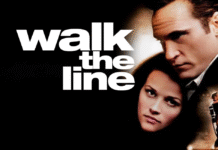

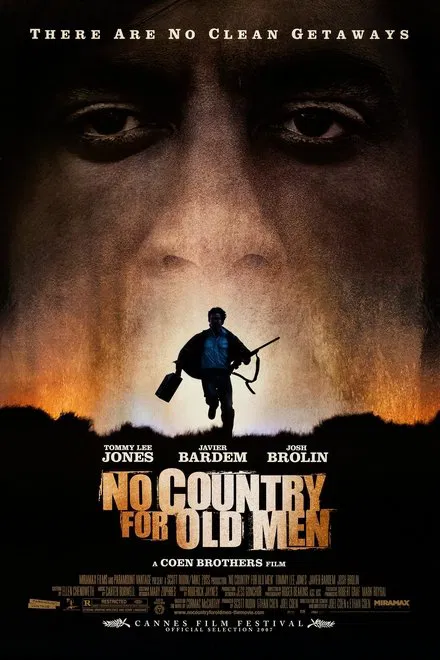

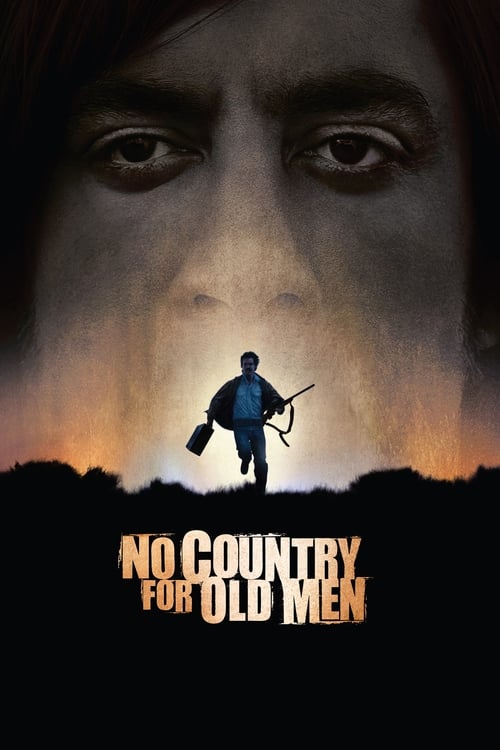

No Country for Old Men (2007): The American Dream Gets a Bullet in the Head

If ever there was a film that made you long for the warmth and comfort of a heroin-riddled Tarantino bloodbath, it’s No Country for Old Men. Directed by the Coen Brothers – the cinematic equivalent of a pair of grinning, existential pranksters – this 2007 neo-western adaptation of Cormac McCarthy’s novel is bleak, beautiful and about as comforting as a concrete pillow.

There are no heroes here. There isn’t even really justice. Just a lot of staring into the middle distance and waiting for something deeply unpleasant to happen. Spoiler: it always does.

Table of Contents

The Plot (Such As It Is): A Briefcase Full of Money and One Really Angry Haircut

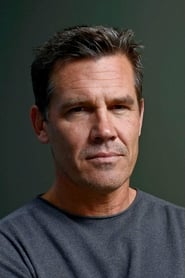

Vietnam vet and blue-collar Texan Llewelyn Moss (Josh Brolin) stumbles across a drug deal gone wrong in the desert. Among the bullet-ridden corpses and heroin lies a briefcase with $2 million. Naturally, he takes it, because morals are for people not living in trailers.

Cue Anton Chigurh (Javier Bardem), a walking migraine with a bowl cut from Satan’s own barber. He wants the money. He also wants to kill everyone who’s ever made eye contact with it. Along the way, ageing sheriff Ed Tom Bell (Tommy Lee Jones) plays grumpy commentary track to the chaos, trying to make sense of a world that now requires Kevlar and psychiatric therapy.

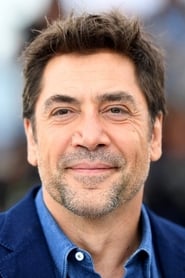

Javier Bardem as Anton Chigurh: Angel of Death Meets Fringe Disaster

Rarely has a character radiated so much menace while looking so much like a disappointed geography teacher. Chigurh is a hitman who operates like an Old Testament god: vengeful, silent and fond of flipping coins to determine who lives and dies.

Bardem’s performance is spine-chilling. He’s calm, collected and utterly deranged. He speaks in riddles, kills with an air gun (seriously), and turns every gas station interaction into a philosophical death match. It’s mesmerising and horrifying, like watching a TED Talk delivered by Satan himself.

Josh Brolin: The Man With a Plan (That Goes Horribly Wrong)

As Llewelyn Moss, Josh Brolin plays the kind of rugged, stoic everyman Hollywood loves to hurl into peril. He’s clever enough to run with the cash, but not quite clever enough to realise he’s being hunted by a one-man apocalypse.

You root for him because he’s got grit. He stitches up his own wounds, improvises weapons and doesn’t say much unless absolutely necessary. Basically, he’s MacGyver with a Texas drawl and less luck.

His descent is inevitable, not because he’s dumb, but because he exists in a universe where logic takes a back seat to nihilism.

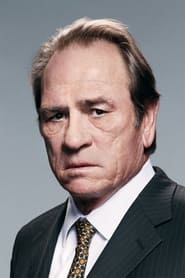

Tommy Lee Jones: America’s Saddest Sheriff

Sheriff Ed Tom Bell spends most of the film squinting into the abyss and mumbling about how everything used to be better before people started blowing each other up for gym bags full of cash.

Jones delivers a weary, world-worn performance that feels like a man trying to catch water with a fishing net. He’s less of a protagonist and more of a philosophical narrator for a society that’s gone off its meds.

His scenes are slow, deliberate and soaked in melancholy. He’s the guy who used to believe in justice but now just wants a cup of coffee and maybe one day without a corpse.

The Coen Brothers: Chaos Architects

Joel and Ethan Coen took Cormac McCarthy’s existential bloodbath and somehow made it even colder. Their direction is ruthless, minimalist and punctuated with bursts of horrifying violence. There’s no music score – just the whistle of the wind and the occasional wet thud of a human life ending.

They take their time. Long silences, lingering shots and that deliciously creeping dread that you know will pay off horribly. It’s masterful filmmaking, assuming your definition of mastery involves maximum audience despair.

Cormac McCarthy: Nihilism in Paperback Form

The story for No Country For Old Men comes from McCarthy, whose novels read like biblical epics rewritten by a particularly eloquent undertaker. There are no heroes. Just men, guns, dust and the kind of dialogue that makes you want to hug your family.

McCarthy’s moral universe is one where justice is irrelevant and order is an illusion. The Coens respect this entirely, resisting the urge to soften anything. Hope is for rom-coms. Here, it gets strangled by a man in a beige jacket with a captive bolt pistol.

Sound Design: The Deafening Roar of Silence

In a cinematic landscape where most films scream at you with Hans Zimmer’s orchestra on steroids, No Country for Old Men dares to whisper. Or rather, not speak at all. The absence of a traditional score turns every creak, footstep and shotgun blast into a sonic gut punch. Silence isn’t just a choice – it’s a weapon. It heightens dread, sharpens focus and makes even the rustle of wind feel like a death omen. If you ever wanted to experience what it’s like to be stalked by inevitability, this is the sound mix for you.

Violence: Sudden, Brutal and Unapologetic

One of the film’s great strengths is how it treats violence. There’s no operatic slow-motion. No soaring strings. Just a man walking down a hallway and another man dying very quickly. It’s clinical. Disturbing. Real.

Chigurh’s weapon of choice – a pressurised air gun normally used to slaughter cattle – is so horrifyingly impersonal it becomes personal. It’s a perfect symbol for the film’s view of death: arbitrary, unfeeling and usually undeserved.

Fate and Coin Tosses: The Philosophy of Dread

At its core, No Country for Old Men is about fate. Chigurh thinks he’s an agent of it, letting coin tosses determine the lives of strangers. It’s absurd. It’s terrifying. It’s also kind of brilliant.

The coin doesn’t really matter. It’s a gimmick. But in a world with no moral compass, even a coin can feel like divine intervention. Chigurh is playing god and the worst part? He’s incredibly good at it.

The Cat-and-Mouse Genre, Deconstructed and Shot in the Head

Most thrillers give you a hero to cheer for and a villain to boo at, ideally with a climactic confrontation where good triumphs, evil gets exploded and everyone can sleep at night. No Country for Old Men sets that formula on fire and dances on the ashes. The cat doesn’t always catch the mouse. Sometimes the mouse dies offscreen, the cat limps away and the cheese was meaningless all along. It’s the cinematic equivalent of setting up a chess game only to be told that all the pieces are dead inside.

Symbolism: Death, Boots and Hotel Curtains

This is a film so soaked in subtext it practically demands an English literature degree. Chigurh’s boots? Always clean. Because he’s above the mess he creates. The hotel curtains? Torn down to obscure view, because clarity and control are illusions. Even the wide-open Texan landscapes feel claustrophobic, as if freedom itself has been flattened by the crushing weight of fate. Every frame doubles as a metaphor, which is fantastic if you enjoy dread disguised as interior decorating.

Carla Jean: Humanity’s Last Gasp

Kelly Macdonald’s Carla Jean, Moss’s wife, is the only character with a shred of genuine moral backbone. Her refusal to play Chigurh’s coin-toss game is both defiant and futile, like trying to outstare a hurricane.

She’s the film’s last grasp at morality and naturally, she’s punished for it. Because No Country for Old Men isn’t just dark – it’s actively mocking you for believing in light.

That Ending: Wait, What?

You think you’re building up to a big showdown. Instead, Moss dies offscreen (thanks), Chigurh limps away with a broken arm and Sheriff Bell talks about a dream. Then the film ends.

That’s it. Credits. Goodnight. Sweet dreams.

It’s as though the film gets bored with traditional storytelling and decides to just walk away, muttering something about futility. It’s anti-climax as an art form. And honestly? It’s kind of genius.

Cinematography: Dust and Despair, Shot Beautifully

Roger Deakins – the high priest of misery captured on film – makes the American Southwest look like purgatory with a postcard filter. The visuals on No Country For Old Men are stunning: sunsets over desolation, motels drenched in decay, every shadow hinting at something horrible.

It’s beautiful in the way a decaying building is beautiful: poignant, fragile and moments from collapse.

The Ending Revisited: Sheriff Bell’s Dream

The final monologue, delivered by a visibly soul-crushed Sheriff Bell, is the film’s last middle finger to narrative convention. He dreams of his father, of fire, of guidance through the darkness. It’s beautiful, tragic and opaque as hell. There’s no catharsis. Just the vague sense that something profound happened and you might understand it if you hadn’t just spent two hours spiraling into despair. It’s the cinematic version of being told “it’s not you, it’s the world.”

The Legacy: Oscars and Existential Dread

No Country for Old Men swept the Oscars, winning Best Picture, Best Director, Best Adapted Screenplay and Best Supporting Actor for Bardem’s haircut. It was a win for art-house nihilism, proving that mainstream audiences could indeed enjoy slow-burning anxiety attacks for entertainment.

It’s now considered one of the best films of the 21st century. Probably because it taps into something universal: the nagging suspicion that everything is awful and getting worse.

Behind the Scenes Trivia: Just in Case You Needed More Dread

- Bardem hated his haircut – as did everyone who saw it. He reportedly said, “You don’t get laid with a haircut like this.”

- No musical score – because emotions are for cowards, apparently.

- Filmed during a Texas sandstorm – which shut down the set of There Will Be Blood next door. Even nature couldn’t handle the existential gloom.

- Cormac McCarthy’s inspiration was real-life drug violence on the Mexican border. Because why fictionalise horror when you can just look outside?

My Final Thoughts: The Desert Will Have Its Due

No Country for Old Men is a slow, meditative film about death, fate and the steady erosion of everything you hold dear. It’s violent without being gory, smart without being smug and nihilistic without being juvenile.

It’s also funny, in that dark, miserable way that makes you laugh just to stop the screaming. Bardem’s Chigurh is one of the great screen villains. Brolin is quietly brilliant. And Tommy Lee Jones deserves an award just for managing to look that disappointed in every scene.

So if you’ve got two hours, an existential crisis brewing and a fondness for bleak masterpieces, this one’s for you.

Just maybe don’t flip a coin over whether to watch it.

If You Like No Country For Old Men, I Recommend These Movies:

- The Road (2009): McCarthy again. Bleaker, if that’s possible.

- There Will Be Blood (2007): Oil, madness and Daniel Day-Lewis screaming about milkshakes.

- Fargo (1996): The Coens go slightly cheerier. Only slightly.

- Blue Ruin (2013): Revenge gets the DIY treatment.

No Country for Old Men

Anton Chigurh

Ed Tom Bell

Llewelyn Moss

Carson Wells

Carla Jean Moss

Wendell

Loretta Bell

Ellis